Songs from Samarkand: a story by Khushbu Khushi

A lush and poetic story by Khushbu Kushi with an original illustration by Mariam Taufeeq.

This story originally appeared in the December 2022 issue of Worlds of Possibility. You can listen to Maya Kanwal narrate the story on spreaker as part of the OMG Julia Podcast, and you can also read the full text below.

Listen to "Songs From Samarkand - a story by Khushbu Khushi" on Spreaker.

Songs from Samarkand

by Khushbu Khushi

1. Baji

I’ve haunted your family since Samarkand. It was the sweetness of your father's words that lured me out from my vow, the reason I followed him as he fled Chengez Khan to the shelter of Sultan Altamash’s Delhi. But the reason I stayed in Delhi was you, Amir.

The day you were born I forgot all about the sweet meadows and melodies of Samarkand, because that day you were the first human to look at me. Not through me, not in my direction. But straight at me. You saw me for what I was and despite that, you smiled at me the widest smile an infant could. You won over whatever I have in place of a heart—had... whatever I had for a heart...

If only I had something else to trade—what I wouldn’t trade to be back with you, even if all I could do was hover over you and watch you work. My sweet, sweet Amir, come find your Baji soon... Hear my songs, if you can. Ya Khudaya, please let him hear my songs…

2. Amir

February 1285

I’ve always remembered your presence as one that has always blessed me in every waking minute of mine—as one that has always been there for me, like a part of my heart that beats with me and breathes with me.

When my mother would pull back the lace curtains of my cot to awaken me, you would be hovering behind her. You would wait so patiently for your turn to give me my morning caresses, even though Fate had ordained you to be someone who couldn’t actually touch me, but only float through me. Your rocky talons for hands, your hollow emerald eyes, your buzzing aura of blue light—none of it ever scared me, Baji. It always made me feel safe, gave me the warmth and assurance of home.

I hope you know that—I want to tell you that. That is why I journeyed to Multan.

This gateway to Hindustan is the center of knowledge—everyone from Baghdad, Arabia, and Persia passes through here on their way to our home of Delhi. I had journeyed against the current of this river of knowledge in the hopes of finding a worthy soul to aid me in my quest. But even if none of the countless scholars who passed through here could not help me—would not help me because they view this quest blasphemous— it doesn’t matter. This is still a city of Saints, and God has graciously brought someone to me who has pointed me in the right direction to find you. That is why I tied the belt of service on my waist and put on the cap of companionship for these five years. I imparted lustre to the water of Multan from the ocean of my wits and pleasantries, in the hopes of spotting a constellation that will guide me towards you, Baji. And tomorrow is the day when I embark to find you—to free you from your prison and repay my debt to you.

But tomorrow is still some hours away, and while His Highness Khan Muhammad is a kind patron, I have excused myself from his court tonight. My mind is too distracted to weave new verses for His Grace—I could try, but they would not be good, because my heart would not be in them. Right now my heart is preoccupied with memories of you. Every time I have spoken to a scholar during these five years, I have thought of you, of the times of my childhood when you would hover in the corner of my father’s study during my language lessons with him. How intently you would listen to me repeat my father’s verses in Arabic, Persian, and Hindavi. How your blue aura would spark up with glee because hearing my father’s verses reminded you of home but, as you used to say, hearing me repeat them was like hearing honey speak. Fate has been kind to me by blessing me with a loving family, and more so for blessing me with the loving presence of a djinn like you, Baji.

March 1285

Since my last entry, I have been journeying north of Multan. It is not ideal for one from the Sultanate of Delhi to venture into Mongol territory, especially during these times, but I have no choice. Just as I have no choice but to seek refuge in these pages, for I received the news of Khan Muhammad’s martyrdom in battle against the Mongols invading our Sultanate a day ago.

Imagine, lying on an open cart, looking at the blue, wispy clouded sky of northern Punjab, watching the green pastures pass-by, day in and day out. Hearing the birds sing their praises for the divine, and this land’s language shape shift with every passing region’s dialect. Some I partially understand; some I can barely comprehend. But this wonder ended yesterday, as I hid in the caravan at the checkpoint. I overheard the soldiers announce it to our caravan leader: New territory they have acquired from the Sultanate, with the added bonus of killing the Sultan’s son, the ruler of the gateway city. The joy this journey had brought me all washed out with my tears.

One elegy I have already composed, but my heart is heavy still. Khan Muhammad’s patronage during my time in Multan was invaluable, without it I would not have been able to afford this caravan of nomads who are transporting me. These nomads know where the Mongols have built their checkpoints, they are familiar enough with the Mongols to negotiate passage with them, and they have a network beyond my comprehension. You would think years of studying under the tutelage of my father, a royal poet, in one of the finest Sultanates ever would make me clever, but the more of the world I see, the more I realise being clever is shallow—it is being humble that brings depth. But I must admit, sometimes I feel like a sheep, being handed off from one caravan to the next for the next leg of the journey, told to hide within their bundles of belongings lest someone spot me. And like a sheep, I am scared—alas, I am only human!

But life is just like this journey; farmlands will warp into mountains or town; languages will shape shift; people will change; day will change to night. But some constants will remain to take me where I am needed.

This caravan’s leader tells me we will be exiting the mountain region soon and I will be handed over to the final caravan—the one who will take me to Samarkand.

3. Baji

Since your birth, I watched over you. When you slept as an infant, I watched the door to your room. When you got older and started sharing your bed with your siblings, I made sure your older brothers gave you space. When you played with the courtiers’ children, I would make sharp objects disappear—why Khudaya does a courtier’s son have a dagger, I still do not understand. All I understood was that I wanted to protect you. To watch you grow. To hear your verses. To learn about the world with you—through you.

There is no reasoning for a djinn to be loyal to a human—especially without a spell, especially for a low-level one like me, especially when it means breaking your vow with the Divine. Perhaps your intellect was your spell, perhaps I am too low-level for this to count as breaking a vow, perhaps the Divine wrote this in our Fate.

I’ve always known you to be a bright child—who else starts poetry at the tender age of nine? But oh, you had more than intellect in you, Amir, and I learned that when you were sixteen. You had started composing your first diwan, Tuhfat us-Sighr.

Everyone was excited for you to begin your journey—everyone except you.

I remember that night so clearly: It was the middle of winter in Delhi, the evening chill had started casting its effect on you humans. You donned a light blue shawl over your white shalwar kameez as you wandered the royal gardens, running your fingers through the mustard flowers. The light from the half moon was so strange that night; there was enough light to make it seem like a full moon, the path was well-lit, and the moonlight bounced off your white clothes, making you seem like a human rendition of an angel. I hovered along silently behind you, observing all of this in awe. What could you be thinking at a time like this? But before I could guess, you turned around and looked at me. Straight into my hollow eyes. You took a deep breath and pointed at me, as if to summon me.

“What do you think of my work?” You spoke in Hindavi.

I looked behind me. No one was there... you were talking to me?

You were talking to me!

“Why-y ... I think it’s brilliant!” I replied in Persian, the only human language I knew.

You smirked and looked at the ground. You were too well-mannered to call out my flattery.

“That is very kind of you. You are a djinn, yes? So you must have witnessed many poets before me. So for you to say that is a high honour for me... But don’t you think, my work could be better?”

“You have your whole life to make it better, my dear Amir. Be patient.”

You blushed at how I addressed you.

“... What shall I call you? Bibi? Baji?”

“... Either is fine”

“But which do you prefer?”

“... Baji.”

“Alright... Baji! Thank you. Alas, I am but a human; my dreams outnumber the years I can hope to live.”

You had turned away to face the moon. You pointed at the stars and started connecting the constellations as you went on:

“I dream of knowing the Divine, of reaching the Divine. Why did the Divine feel it necessary to bestow the night sky with stars? Why does the sea yearn for the shore? Where is the seventh sky? Why did the Divine bless me with dreams of meadows I have never seen? Why do I hear praises sung in Persian? There must be some reasoning behind it; a part of me thinks I can reach that reasoning, but a part of me feels so restricted by who I am...”

I didn’t know what to say to you. But I felt something in my torso, I felt something beat loud, as if to send me a message.

“Do you have dreams, Baji?” You broke out of your reverie to face me.

“No... Djinns don’t sleep”

“... Don’t djinns get tired?”

Your eyes had widened at this revelation... and oh Khudaya, it was a revelation. Humans aren’t supposed to know about our kind, and I felt the repercussions for it when my own aura of electricity struck me. But you couldn’t see that. Just as you couldn’t see that my mythical mind had already started conjuring the path you were in search of, Amir. I may not have known what to say, but I knew what to do.

So, for the first time in your existence on this earth, I left your side. You didn’t notice because you were asleep, because in human hours it was only a few hours. But for me the journey was long, as I summoned a gate back to Samarkand.

I fought through the current of djinns travelling back and forth between Samarkand and Delhi, travelling through floors and gates no low-level djinn could access without it draining my aura. When I finally reached Samarkand— oh Samarkand! The meadows, the poetry, the architecture—it reenergised me enough to dredge on.

It may sound silly to you humans, but our kind and our world, despite its different rules, isn’t that different from yours. Just like your world, djinns have friends, like the ones I left behind in Samarkand. And just like your world, sometimes friends think you’re mad when you return after a long time, that too with a crazy request.

It wasn’t that crazy—I had only asked to meet before the council of djinns of Samarkand—you know, like the councils that your kind has... Except ours are more powerful because they share direct connections to angels, saints, and others more Divine. And only high-level djinns can ask for an audience with them... Okay, yes, I know. It truly does seem mad. But, Amir, being with you had helped to learn many things, including the thing that you humans call ambition. And I knew, from years of witnessing how the courtiers pranced around royalty, that having ambition sometimes means having no self-respect because there are things you love more than yourself.

So I begged my friends, they pointed me to other djinns, and through this process of being a rare djinn who begs, I found myself before the council. A group of djinns, all glowing red, faces hidden, perched high above me, with voices that didn’t sound like voices but thunder, led by my kind’s master.

I bowed, I thanked them for their time, I withstood their insulting remarks about my pedigree, and then I asked for them to hear my plea—to bless my Amir with the key to unlock the door of knowledge he seeked, the door that would grant him the kind of wisdom and eloquence that would resound through history—that history couldn’t forget him even if it tried. They will sing your name until the Last Day, I promised, because even my kind can recognise when a human is different—is special.

And so they agreed to give me the key, but in exchange I had to give something of my own. But what did I have to offer? I had no physical possessions, no grand spells or mesmerising talents like the higher level djinns. I only had what I had learned from the humans... and this beating heart that had forced me to endure the return to Samarkand.

You should’ve seen the djinns at that moment, Amir. They laughed at me! A djinn who gives away their heart and stays away from it is not a djinn, cannot remain a djinn. But it is a steady decline, so I had time, and I took my chances.

I stood before the leader of the council as his golden talons recited a verse and reached into my torso. For the first time in my seven-hundred-years of existence, I blacked out. When I came too, I was back in Delhi, back in that same garden of mustard flowers, with the key buzzing in place of my heart.

From the moment you awoke the next day, until the moment I was imprisoned, it was all a blur of rushing to bestow as much knowledge as I could before my time ran out. To push you towards the verses that would mesmerise; to point you to the music you could create. Others would get overwhelmed, but you took it so well— in your stride Amir, just like you dreamed, and just like you were destined to.

You honoured your father’s heritage by innovating Persian poetry into eleven new genres. You honoured your mother’s heritage by beginning the tradition of the ghazal in Hindavi. You combined your knowledge to create the devotional music of qawali for your homeland. You rebirthed the veena into the sitar; divided the dhol into the tabla; challenged the raag with the tarana and trivat. The Divine had finally blessed you with the ability to grasp the things that had eluded you; planes you had dreamed of reaching were now the planes your mind could access. And the little boy everyone called Abul Hasan became known as Amir Khusro, the voice of Hindustan.

Even the guards of my prison talk about you Amir, imagine! Djinns in another realm talk about you, talk about visiting Delhi to witness the vision that is you. That is how I know my part is done, and while I sit here thinking of you, I hope you know that I have no regrets, that I would do it all again to see you thrive. That your Baji is so proud of you. That is why I sing, so you know that I am proud of you.

4. Amir

April 1285

After taking the longer route to avoid the Mongols, switching more caravans than I had anticipated, I am finally here, Baji. In the land of my ancestors, Samarkand.

It is so strange, to wander through a wonderous city without caring for the wonder. I know Samarkand is on par with Baghdad, Multan, Delhi. Some say this city is above us, that angels bless the scholars of this city—scholars who are studying subjects that entice a part of me, that is before I silence it. Before I remember that beyond the turquoise blue domes and floral blue tilework, beyond the sweet scent of the air that carries the praises sung by near-Divine voices, this is the city my father fled—this is the city that holds you captive. And beyond the appearance of these pure-hearted scholars who mingle in the open, there are those who wander in the shadows— those who tread the line of divine and human.

So I escape into the cool shadows of the turquoise domes. I may not be clever, but living in the shadows of royals teaches you enough about where to look. And I found them, dressed in pink robes, face veiled with Chinese silk, donning ruby glasses, the type that the rulers of Hindustan wear—ruby glasses that hid intensely red, hollow eyes.

They introduced themselves as Aab. They knew I was in search of you, Baji, for they addressed me by name before I could introduce myself. The conversation was brief and precise: They asked me for place, time, and method, so I told them.

Five years ago, in the mustard flower garden while I was composing a ghazal with you sitting beside me. A portal opened to reveal a red djinn whose voice thundered that you had broken your vow with the Divine by not only engaging with me but helping me, consequently interfering with Fate. Before I could object the portal began to turn you to ash and pull your ashes in. I reached for your hands, but my hands could not grasp your talons. I jumped straight through you and the portal, landing harshly on all fours. By the time I turned around you were gone. But I had heard what you had said. “Amir, listen for my song.”

Aab took a deep breath and sighed. They said it wasn’t possible to save you. I persisted. They repeated. I persisted. They repeated with a firey glow that escaped their silken veil. I stood my ground. So they told me the truth.

The truth being that this is a Divine order, one from above the seventh sky. It is allbinding, and no one of any level of magical ability can do anything about it—never has been able to do anything about it. So even if Aab wanted to help me, they couldn’t. There was no method because no one had done it before.

I entreated—there must be some way, something. Aab pointed me to a path that they said would lead me to you, that is if I was destined to withstand the path. So I began the journey with nothing but this journal, a bottle of rose water, and the clothes I had on my back.

It was an unbeaten path out of the city, to the meadows, the kind I had seen in my dreams when I was young. And in the center of a meadow there was a barren circle. At first I thought I had been fooled, but then I heard the wind, and in the wind, I heard your voice, Baji. So I sat down, and I’ve been sitting here ever since. Day has broken down into night. A half-moon gives me the light to write this entry, and my heart tells me to will an audience with the forces that took you from me.

5. Aab

Humans say Fate works in mysterious ways, for them saying that suffices. But for us, Fate is methodical, Fate is precise, Fate was decided before the seven skies were even formed. Everything is destined, from the things we do to the things we don’t do. Fate adjusts the currents to keep us sailing towards what we were destined for, because all of us are destined for something.

Some of us are destined to love without ever knowing love ourselves. Some of us are destined to live a simple life, which seems like the best destiny at times. Some of us are destined to witness what Fate has destined for others. And lastly, some of us are destined to embrace greatness in every form that Fate has destined it for us, because the Divine has willed it. And greatness, mind you, is not always what you humans think of as wealth and glory, no.

The truest forms of greatness are the purest forms of love and devotion. The kind of love the Baji had for her little Amir, and the kind of devotion Amir was destined to have—the kind of devotion that would see us witness him sitting in the middle of a field, lit by nothing but moonlight, calling upon the Divine to hear his plea.

And me? I was destined to witness it so I could tell you, so hush, and listen.

I knew who Amir was the moment I saw him. I knew what he wanted was impossible, but I also knew from his aura he was different from other humans, that he had the purity in him to evoke things other humans that had come to me cannot. So I pointed him to this field near Samarkand where it is said those from above the seventh sky enter. And I followed him from above in the shape of a bird. And I sat with him for hours watching him write his journal, before putting it away and standing up, and listening. So I too began to listen.

Listen to the song she sings. Listen to his plea. And then I listened to how their voices combined—how love and devotion combine. And I saw—saw how that unlocked a portal below Amir’s feet, how stars like the night sky floated below him in a pool of bright blue light. I saw how Amir’s devotion to the Divine was so pure that he somehow withstood the pain this portal caused his fragile human body.

While I abandoned my bird form and sheltered my eyes with my ruby glasses, I saw how Amir’s devotion was so pure it could recognise and treasure another form of purity: Love. I saw Amir’s body be energised, his eyes that were shut in pain opened to let out beams of light. And then a great darkness ensued, one that even I could not see in. I knew what it was, Who it was.

When the darkness subsided and the moonlight returned, I rose to my feet and walked to the center of the meadow. And there was Amir, lying on the ground half awake, with a smile on his face mumbling in the language of his homeland— mumbling to a woman who seemed a little older than him, one with a blue aura of electricity, hollow emerald eyes, and talons for hands. Hands that Amir happily held.

About the Author

Khushbu Khushi (she/they) is a speculative artist and writer from Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan. Working in tech by day, she juggles her art, design, and writing practices by night, all of which share a post-colonial and queer lens. When not creating, Khushbu enjoys gardening, reading POC-centric fiction, playing indie video games, being a part of Tasavvurnama.com, and listening to lo-fi music. To see what else they’re up to, find them on Instagram as @Mushbagram or Twitter @HeyMushba.

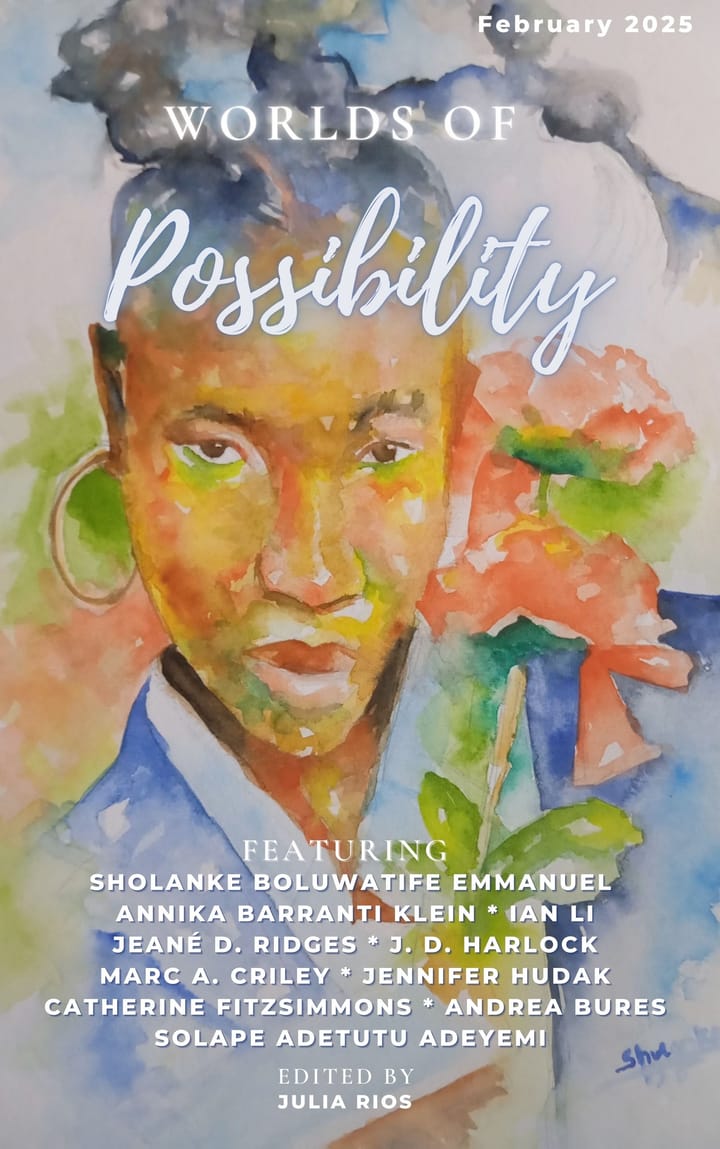

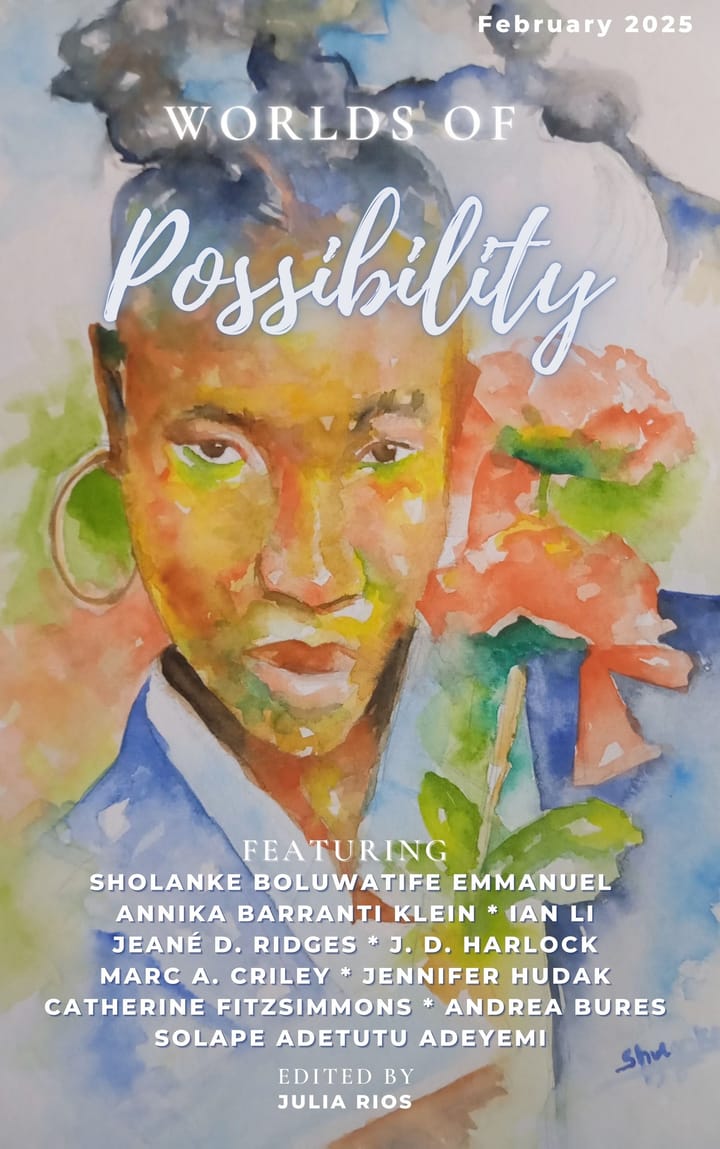

About the Artist (and the art)

Mariam Taufeeq is an illustrator and writer from Pakistan. She enjoys telling stories, no matter the medium, and has a deep adoration for weird science-fiction and fantasy.

About the illustration: This illustration is of the scene when Baji and Amir meet directly for the first time, in the royal gardens of Delhi. A brown, rectangular frame-border (in the style of classic Persian illuminations) surrounds the image. Only Baji’s wispy form spills beyond the bounds of this frame, hinting at how her relationship with Amir is something that sends order reeling into chaos, the force of her love being uncontainable. Also in the style of classic Persian illuminations, a brown box containing a verse (from Amir Khusro himself) marks the lower half of the frame-border. It reads:

“Khusrau darya prem ka, ulti wa ki dhaar,

Jo utra so doob gaya, jo dooba so paar.”

(“Oh Khusrau, the river of love

Runs in strange ways.

One who enters it drowns,

And one who drowns, gets across.”)

About the Narrator

Maya Kanwal is a Pakistani-American writer from Houston, TX and fiction editor at Gulf Coast Journal. Her own work appears in Witness Magazine, Meridian, Quarterly West, and other journals, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She is winner of a 2022 Inprint Donald Barthelme Prize in Fiction and Witness Magazine 2022 Literary Awards runner-up. You can find her on Twitter @mayakanwal

Support Worlds of Possibility

If you are enjoying Worlds of Possibility, please consider supporting by becoming a paid subscriber through this website. Paid subscribers get early access to issues of Worlds of Possibility in ebook format. If you can't afford that, you can also support by subscribing for free to the OMG Julia Podcast and having episodes delivered directly to your podcatcher of choice. Every little bit helps me continue to pay creators for their stories, art, poetry, and more!